By COLE SINANIAN | news@queensledger.com

The moment Bryan Kelly began speaking, several of the more than a hundred Greenpointers packed into the Polish Slavic Center solemnly pulled out their signs: “600ft Luxury Towers? Hard Pass,” read one.

“Bushwick Inlet Can’t Be Replaced,” read another.

Tensions in the room were high. Kelly, President of Development at the Gotham Corporation, had come to pitch an enormous mixed-use development that would add 3,000 residents to Greenpoint by its completion in the early 2030s. The sign-bearers had come to voice their disapproval before the Community Board.

Hanging in the balance is the fate of Monitor Point, a spit of land north of Bushwick Inlet that’s Greenpoint’s last swath of undeveloped waterfront. A section of it is part of a 27.8-acre parcel that the City set aside in the 2005 Williamsburg/Greenpoint rezoning for the long-awaited Bushwick Inlet Park.

Local activists with Save the Inlet and Friends of Bushwick Inlet Park have fought for years to prevent private developers from acquiring the promised parkland. Twenty years later, the Gotham Organization — in collaboration with the MTA — is seeking to remove the park designation from the City Map and upzone the adjacent property in order to build three high-rise apartment buildings, the tallest of which would rise to 600ft. The three towers would include 1,150 housing units, 40% of which would be affordable at 40-80% Area Median Income (AMI), and could add some 3,000 residents to the neighborhood. These towers, developers say, would provide much-needed affordable housing to the district, and help fund major public benefits, like a building to house the Greenpoint Monitor Museum, public waterfront access, shoreline rehabilitation, and crucial MTA funding.

But critics argue that the project is a land-grab. The 80,000-square-foot MTA-owned property located at 40 Quay Street will be leased to the Gotham Organization for a century, while air rights at the Greenpoint Monitor Museum-owned 56 Quay Street — designated on the City Map as park land but never acquired by the City — will be acquired by Gotham. It’s a betrayal, critics say, of the City’s 2005 commitment to integrating the land into Bushwick Inlet Park.

Other critics are longtime Greenpoint residents with the trauma of the displacement and gentrification brought by the 2005 rezoning and the luxury high-rises that followed fresh in mind, fearing that such a population bump of mostly wealthy residents will only lead to more gentrification. And for others still, it’s an environmental issue; rare birds and sea life live around the Inlet, which was just a century ago toxic with pollution. Now, years of care and rehabilitation have allowed the public to access the estuary once again, just in time to be overshadowed by residential skyscrapers that activists fear could turn the park and the Inlet into little more than a playground for the wealthy.

Still, several groups in attendance came to support the Monitor Point project, including the labor unions SEIU 32BJ and Local 79, whose workers expect it to bring them good jobs, as well as Los Sures, a local Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) cooperative.

The hearing, held on January 20, was the beginning of the project’s ULURP, set to go before Community Board 1 for a recommendation vote on February 3.

Affordable for who?

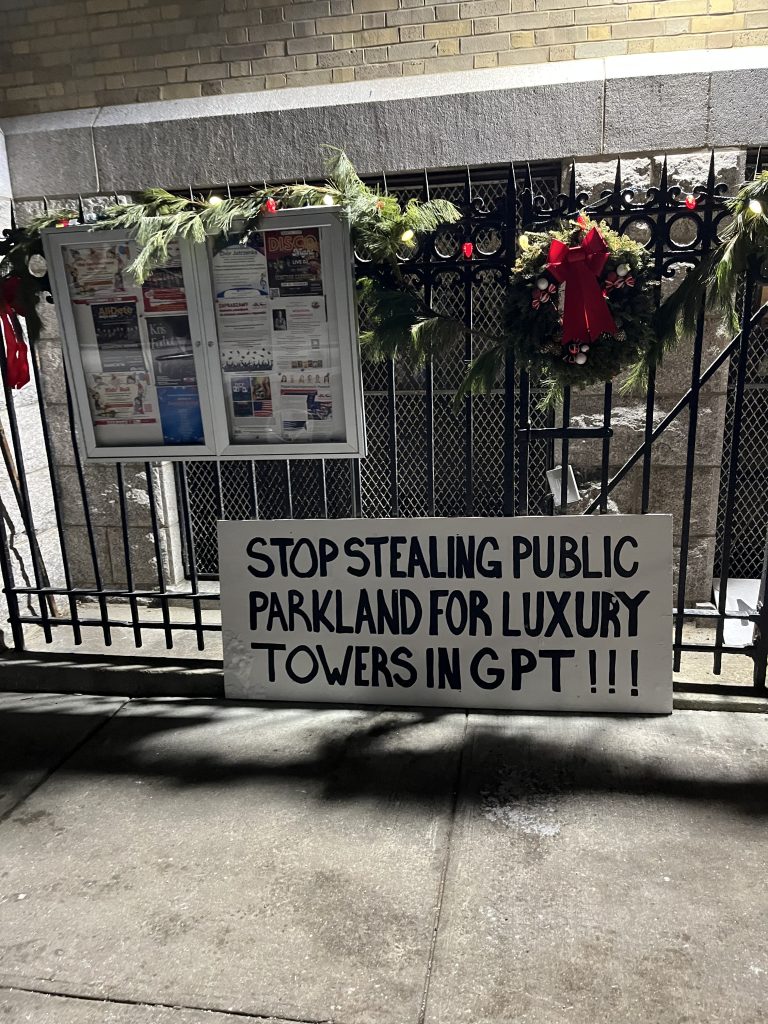

Outside the Polish Slavic Center, activists with Save the Inlet rallied before the hearing, braving the cold to chant and hold signs that read “Public Land for Public Good!” and “Stop Stealing Public Parkland for Luxury Towers in GPT!!!”

Inside, developers began by presenting their vision for an integrated, mixed-used community space that would finally connect Bushwick Inlet Park, the East River, the Greenpoint Monitor Museum, and the rest of the North Brooklyn waterfront esplanade via a series of public walkways and open spaces, while restoring a degraded and flood-vulnerable shoreline on Greenpoint’s last remaining plot of undeveloped waterfront. They argued the project goes far beyond housing, and will unlock more than 50,000 square feet of public open space that would include retail, park land, public plazas and lobbies, and the Greenpoint Monitor Museum itself. Part of this is a $20 million investment in “site resiliency, waterfront infrastructure, and pedestrian connections.”

“It adds 51,500 square feet of new open space — some of which was expected in the ‘05 rezoning and more — for the community, for public equity, not just for residents of the new building,” said Kelly. “It’s an open gate to the community, not a gated community.”

It would be all connected by a meandering path inspired by Bushwick Inlet that would finally connect the Williamsburg and Greenpoint waterfronts. Dan Kaplan, senior partner with FX Collaborative Architects, said that the project’s architects were working on a “bird-friendly” design that would integrate texture and setbacks into the buildings to avoid bird collisions, and that an all-glass facade would be avoided “at all costs.”

The 690 units of luxury housing would finance the public benefit, developers said, like an additional 460 units of “permanently affordable” housing at 40-80% Area Median Income (AMI), publicly accessible “open space,” and an expanded Greenpoint Monitor Museum. Key to the development team’s presentation was that the land’s current use — housing a degraded MTA mobile wash warehouse — adds nothing to the community, prevents the public from accessing the waterfront, and won’t protect the shoreline from the effects of erosion and climate change. And in leasing its property to the Gotham Organization, the MTA will earn more than $600 million over the course of the lease that could be put towards transit improvements throughout the city. Money for Bushwick Inlet Park, meanwhile, will begin at $300,000 annually, and increase over the course of the 99-year lease.

Throughout their presentation, the development team repeated that their plan does more for the community than is required by law. At 40% affordable housing at 40-80% AMI, the Monitor Point towers will far exceed the 25% affordability at 60% AMI requirement in the City’s mandatory inclusionary housing law, Kelly pointed out.

“We have had about 150 outreach meetings,” he said. “That’s to your elected officials, religious organizations, civics, friends of open space, people who are not friends of the project, and people who are friends of the project. Because the result is, we’ve done our best so far to make changes to address your concerns, and that concern is 40% affordability.”

Restler weighs in

Much of the public, however, was unimpressed. While Kelly was explaining the annual park funding, some audience members shook their heads and shouted “shame!” When he said that the towers would stand 56, 40, and 20 storeys, respectively, someone in the crowd shouted “Way too high!” And as Kelly explained the goal of the project — to create “intergenerational, mixed income housing and ultimately fighting for the goal of creating open space for everybody,” he said — shouts rang out from the audience: “Liar! Liar!”

At several points throughout, Community Board 1 Second Vice Chair Del Teague, who moderated the hearing, had to silence unruly audience members.

“We have 85 people who want to speak,” Teague said. “I don’t even know if I can give people a full minute.”

The mood turned, however, when Greenpoint City councilmember Lincoln Restler — whose City Council vote will likely determine the fate of the project — got up to speak.

“I want to just say plainly where I’m at on this project to all of you, which is precisely what I’ve said to Gotham and the MTA,” Restler said. “I’m a no on this project.”

A raucous applause broke out before he’d even finished the sentence. Some audience members were on their feet in standing ovation. Kelly and the development team, meanwhile, looked uncomfortable as they retreated into the shadows in the room’s far corner. Someone catcalled: “Atta boy, Lincoln!” After about 30 seconds of applause, Restler approached the mic again:

“We built significantly more new housing in our district than any other district in the city,” he said. “We built well over 26,000 units of housing, but the vast majority of that housing is market rate, luxury housing, housing that our communities quite simply can’t afford.”

He continued: “This is the last large public site in Greenpoint, and the idea that we would build predominantly luxury housing on this site, I have to say, I find it offensive. This was the central jewel of the Greenpoint Williamsburg rezoning. And 20 years later, we do not have a fully funded park. In fact, most of the park is in need of significant remediation before we see construction move forward.”

Union jobs, Trojan horse

After Restler’s speech, the some 85 members of the public who’d signed up to speak lined up in waves to deliver their testimonies. First up was the SEIU 32BJ union, which represents building maintenance workers. Several members attended the hearing to express their support for the project, which they argued would deliver reliable, well-paid union jobs to working-class Brooklynites.

“I’m happy to report that developers of this proposed project have made a credible commitment to good jobs at the project,” said Theodore Perez, a worker with SEIU 32BJ. “Good Jobs mean prevailing wages. They mean benefits, and they mean a pathway to the middle class for the people who work them. We need housing built in every neighborhood in New York City to ensure that working families are not displaced by dwindling supply and skyrocketing rents.”

According to an unnamed Gotham Organization spokesperson, communicated via William Roberts with a PR firm called Berlin Rosen, both the unions SEIU 32BJ and Local 79 — which was also present at the hearing — have partnerships with the company that guarantee union employment at all Gotham properties.

“32BJ and Local 79 have been longtime partners of The Gotham Organization,” the spokesperson wrote. “All Gotham-owned buildings are staffed by 32BJ members, and we have worked closely with Local 79 across numerous housing projects. We look forward to continuing this partnership with Monitor Point.”

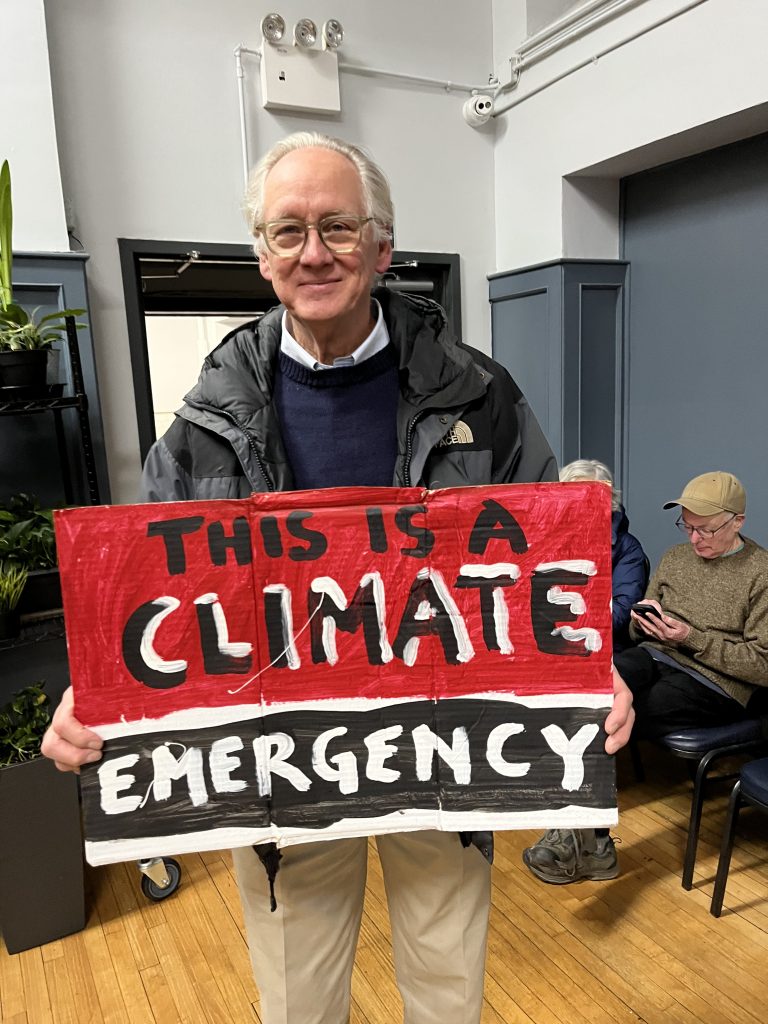

Sarah Roberts, also known as “the Brooklyn Bird Lady,” opposed the project on ecological grounds:

“I am here to oppose the proposed Monitor Point development not because I dislike change or I don’t want affordable housing,” but because we must protect what is truly irreplaceable,” Roberts said.

“Bushwick Inlet is not just another piece of industrial shoreline,” she continued. “These tidal wetlands provide natural climate resilience. They slow down storm surge, absorb blood water, store carbon and buffer our community from increasingly frequent and severe weather events

George Weinmann, Vice President of the Greenpoint Monitor Museum, testified in support of the project, highlighting the educational value of the museum, which showcases the USS Monitor, the legendary Civil War battleship that was built in Greenpoint. Weinmann traced his family history in Greenpoint back to his ancestors who fought in the Revolutionary War, and explained how local children recognize him and his wife, Janice — who serves as the museum’s president — on the street as the “Monitor people.”

“We tell them that we are going to build a museum on the land that shares the launch site of the USS Monitor, the ship that saved the Union, and we don’t want to disappoint them,” Weinmann said. “Please approve and make the Monitor Museum a reality.”

Chris Duerr, a longtime Greenpointer and father, had a different take. He described how his son was eight-years-old in 2016 when Mayor de Blasio assured the community it would get the full, 27.8-acre Bushwick Inlet Park. Now, his son’s off to college, Duerr said, and the full park still isn’t built.

“This is not about affordable housing,” he said. “Affordable housing and this museum are the Trojan Horse for luxury tower development.”

Duerr continued, addressing Gotham directly: “The plans that you guys presented are very compelling, but we’ve seen a lot of plans, and we would appreciate not being gaslit one more time.”